Family voucher programs: an ethical way to increase non-directed kidney donation

Alexander Capron1, Jeffrey L. Veale2, Nima Nassiri2.

1Gould School of Law and Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, United States; 2Department of Urology, David Geffen School of Medicine, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Kidney transplant “vouchers” were created in 2014 as a means to overcome the “chronological incompatibility” that arises when a potential donor wants or needs to donate before the relative or friend who is to receive the kidney is ready to have a transplant. In exchange for the donor giving a kidney now, the prospective recipient is provided with what the National Kidney Registry (NKR) calls a “Standard Voucher” (SV), which can be redeemed when the recipient is ready for a transplant. In this paper, we describe the benefits of extending this innovation to altruistic donation and examine preliminary data on the effects.

The kidneys supplied by altruistic donors are critical to the success of transplant chains because they typically serve as a non-directed donation that sets in motion a chain of many biologically incompatible donor-recipient pairs . Well-designed chains make possible a large number of transplants which would otherwise not have occurred or would have taken much longer to arrange, especially for highly sensitized or O blood-type recipients. The innovation—termed “Family Vouchers” (FVs) by the NKR— overcomes the “sentimental incompatibility” that leads some potential altruistic donors to back away from donating when they realize that giving a kidney to a stranger now will preclude them from providing a kidney should a loved one need a transplant in the future. FVs differ from SVs because donors are permitted to list up to five intended recipients, though only one may redeem the FV, and the intended recipients do not then have terminal kidney disease and may not develop it in the future. Like SVs, FV-based donors initiate kidney chains, which end with a recipient who lacks a donor. Likewise, the transplant network that issues the voucher will provide a suitable kidney at the end of a future chain when the designated recipient redeems the voucher.

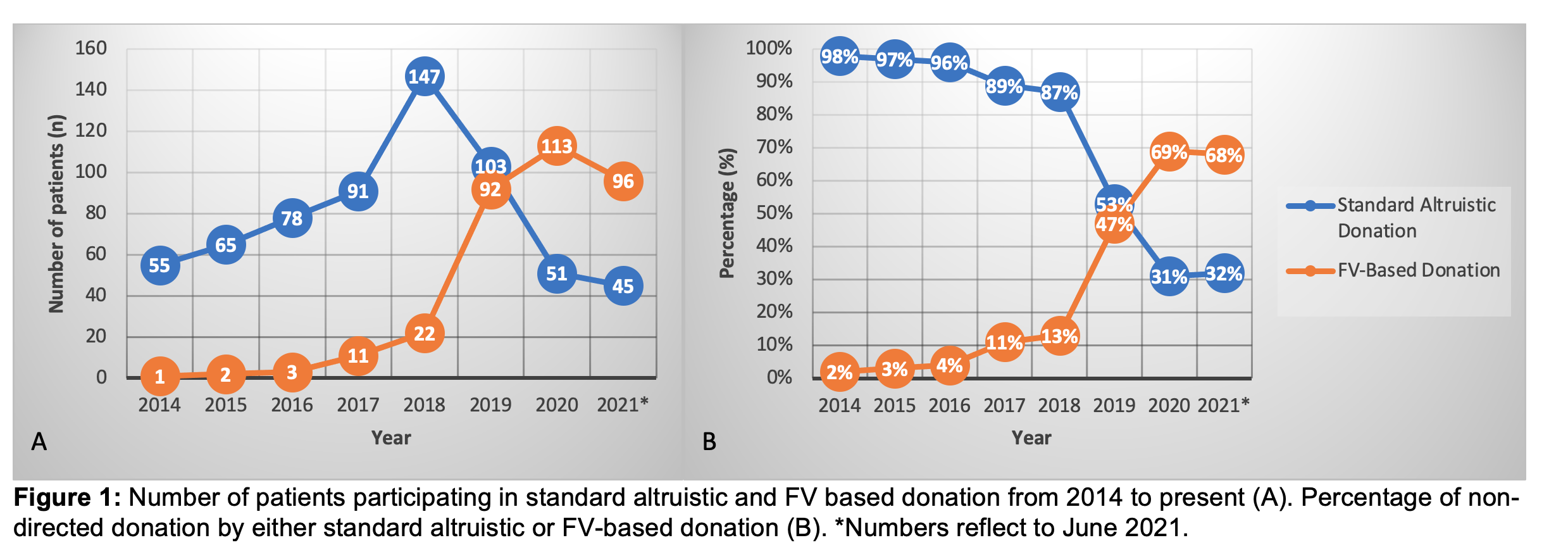

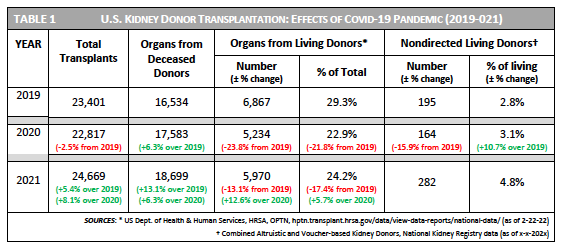

The expectation that FVs will attract new donors as well as provide assurance to people who develop doubts about their plan to make an altruistic donation is supported by current data. For example, voucher-based donation, which accounted for a tiny fraction of nondirected donation in the U.S. when it began in 2014 had surpassed altruistic donation by 2019, and its rapid growth helped nondirected donation to triple by 2021 (Figure 1). The Covid-19 pandemic interrupted this steady rise, but the decrease in nondirected donation was much smaller than for living kidney donation generally (Table 1). While altruistic donation went down, the rise in FV-based donations meant that in 2021 the percentage of living donors who were nondirected was the highest ever. Family Voucher programs, which are aligned with a central goal of transplant professionals—shortening the wait for transplants—need to broaden their outreach in minority communities and to carefully self-monitor their ability always to fulfill their moral commitment to provide all voucher-holders with a kidney from a suitable living donor.

right-click to download